England

Football Online England

Football Online |

|

|

Page Last Updated 6 May 2024 |

Alba |

|

|

13 vs.

Scotland

previous match

(21 days)

14 vs.

Ireland

|

15 |

|

next match

(two days)

16 vs.

Wales

19 vs. Scotland |

Saturday,

11 March 1882

Association Friendly Match

Scotland 5

England 1

[2-1]

|

.jpg) |

|

|

Hampden Park, Hampden Terrace, Prospect Hill, Glasgow,

Lanarkshire

Kick-off (GMT):

'soon after half-past three'

Attendance:

'estimated that 10,000 persons were inside

the ground'; 'before about 12,000 spectators'; 'presence of 12,000

spectators'. |

|

England's third and final visit to Hampden Park, all defeats;

England's sixth visit to Glasgow, to Lanarkshire and to Scotland,

still without a victory |

|

Charles Campbell won the toss |

Arthur Brown

kicked-off |

|

[0-0] McIntyre free-kick scores:

disallowed

[1-0] William Harrower

15

'shot through'

- an appeal for offside was

allowed by England's umpire, but not upheld by the referee.

| England's fourth

ever equalising goal> |

[2-1] Geordie Kerr

43

'placed' |

[1≡1]

Howard

Vaughton

35

'Gillespie

caught it with his foot, he slipped and the ball was smartly put thro

by Vaughton' |

[3-1] Robert McPherson

46

'kicked' -

disputed but allowed by the referee

[4-1] Geordie Kerr

70

'beautiful shot'

[5-1]

Johnny Kay 85

'sent the ball through'

- offside, allowed by the ref. |

[5-1] after a

scrimmage the ball hit the post |

|

|

Played according to FA rules. |

|

|

|

|

flg.jpg) Match

Summary Match

Summary |

|

Officials

[umpires and referees are of equal relevance] |

|

Team Records

|

England |

|

Umpires

|

An experimental law is introduced, that empowers the referee to award a goal

in cases where, in his opinion, a goal has been prevented from a deliberate

handball by the defending team. It lasts one season only, and it is

unknown as to whether it resulted in any England goals in 1881-82. |

Segar

Richard

Bastard

28

(25 January 1854)

Upton Park FC

(replaced Major Marindin) |

Thomas Anderson

(Renfrew

FC President) |

|

played against Scotland in 1880 |

Referee

John Wallace

Third Lanark RV, Beith (SFA vice-president). |

|

|

|

|

Scotland

Team Scotland

Team |

| |

|

Rank |

No official ranking system established;

ELO rating

1st |

Colours |

'the Scotchmen having adopted a new jersey, the

well-known blue and white stripes of the Edinburgh Academicals, with the

Scottish lion worked in gold as a badge.' |

|

Captain |

Charles Campbell |

Selection |

The Scottish Football Association

Selection Committee |

|

P 7 of 8, W 6 - D 0 - L 1 - F 31 - A 10 |

team chosen following a trial match on Tuesday, 7 March 1882 |

|

"The committee do not chose players because they

play well in a trial match; they choose them on the form revealed throughout

the season." - Wednesday, 8 March,

1882, The Athletic News |

Scotland

Lineup Scotland

Lineup |

|

|

Gillespie, George |

23

344 days |

1 April 1858 |

G |

Rangers FC |

4 |

4ᵍᵃ |

|

|

Watson, Andrew |

25

291 days |

24 May 1856

in Demerara, British Guiana |

RB |

Queen's Park FC |

3 |

0 |

|

final app

1881-82 |

|

|

McIntyre, Andrew |

26

214 days |

9 August 1855 |

LB |

Vale of Leven FC |

2 |

0 |

|

|

Campbell, Charles |

28

50 days |

20 January 1854 |

Half

Back |

Queen's Park FC |

9 |

1 |

|

63 |

|

Miller, Peter |

24

37 days |

2 February 1858 |

Dumbarton FC |

1 |

0 |

|

|

Fraser, Malcolm John Eadie |

22

7 days |

4 March 1860

in Ontario, Canada |

OR |

Queen's Park FC |

2 |

0 |

|

64 |

|

Anderson, William |

19

320 days |

25 April 1862 |

IR |

Queen's Park FC |

1 |

0 |

|

Kerr,

George |

22

13 days |

26 February 1860 |

Centre

Forward |

Queen's Park FC |

4 |

9 |

|

65 |

|

Harrower,

William |

20

144 days |

18 October 1861 |

Queen's Park FC |

1 |

1 |

|

tenth debutant to score against England |

|

Kay,

John Leck |

24

186 days |

6 September 1857 |

IL |

Queen's Park FC |

2 |

2 |

|

66 |

|

McPherson,

Robert |

22

269 days |

15 June 1858 |

OL |

Arthurlie FC |

1 |

1 |

|

only app

1882 |

|

reserves: |

not known |

|

team notes: |

George Kerr is often

found as Ker in history books - but definitely baptised a Kerr in

Govan. He is the younger brother of William,

who played

for Scotland in the first two fixtures.

The seven Queen's Park

FC players were all playing on their home ground. |

|

records: |

George Kerr has now scored

seven

goals against England, making him the record opposing goalscorer. |

|

|

|

2-2-6 |

Gillespie -

Watson, MacIntyre -

Campbell, Miller -

Fraser, Anderson, Kerr, Harrower, Kay, McPherson. |

|

Averages: |

Age |

23

years 270 days |

Appearances/Goals |

2.7 |

0.7 |

|

|

|

|

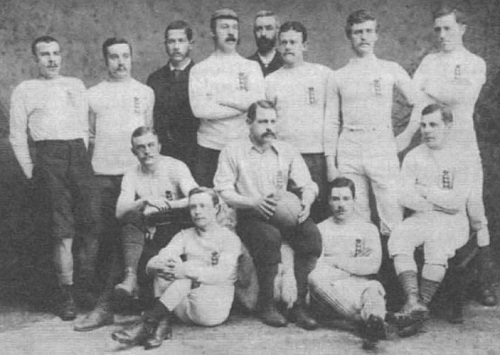

flg.jpg) England

Team England

Team |

| |

|

Rank |

No official ranking system established;

ELO rating

2nd |

Colours |

'dressed in white jerseys and blue knickerbockers' |

|

Captain |

Norman Bailey |

Selection |

Following a

trial match,

The Football Association Committee, with Secretary Charles W. Alcock having the primary

influence |

|

P 2 of 15, W 0 - D 0 - L 2 - F 2 - A 11. |

P 15 of 31, W 5 - D 2 - L 8 - F 39 - A 43. |

|

|

two teams were chosen at 23 Paternaster Row on Tuesday, 7 March

1882. |

flg.jpg) England

Lineup England

Lineup

(a record-equalling

low six changes to the previous match) |

|

|

Swepstone, H. Albemarle |

23

56 days |

14 January 1859 |

G |

Pilgrims FC &

Corinthians FC |

2 |

10ᵍᵃ |

|

=most gk apps |

|

|

Greenwood, Doctor

H.,

injured |

21

131 days |

31 October 1860 |

RB |

Blackburn Rovers FC |

2 |

0 |

|

final app 1882 |

|

97 |

|

Jones,

Alfred |

21

55 days |

15 January 1861 |

LB |

Walsall Swifts FC |

1 |

0 |

|

|

Bailey, Norman

C. |

24

231 days |

23 July 1857 |

Half

Back |

Clapham Rovers FC |

6 |

0 |

|

|

Hunter,

John |

30

210 days |

13 August 1851 |

Heeley FC,

Providence FC,

Wednesday FC &

Sheffield Albion FC |

6 |

0 |

|

|

Cursham,

Henry A. |

22

104 days |

27 November 1859 |

OR |

Notts County FC &

Corinthians FC |

3 |

1 |

|

|

Parry, Edward

H. |

26

321 days |

24 April 1855

in Toronto, Canada |

IR |

Old Carthusians

AFC, Swifts FC &

Remnants FC |

2 |

0 |

|

Vaughton,

O. Howard |

21

61 days |

9 January 1861 |

Centre

Forward |

Aston Villa FC |

2 |

6 |

|

=mst

gls |

|

|

Brown,

Arthur |

23

98 days |

3 December 1858 |

Aston Villa FC |

2 |

4 |

|

|

Bambridge,

E. Charles |

23

224 days |

30 July 1858 |

IL |

Swifts FC |

5 |

6 |

|

=mst gls |

|

|

Mosforth,

William |

24

68 days |

2 January 1858 |

OL |

Wednesday FC |

8 |

2 |

|

mst apps |

|

reserves: |

Arthur Mallinson (Barnsley Wanderers FC &

Heeley FC,

goal),

Edwin Buttery (Heeley

FC, half-back),

William Page,

Ernest Wilson (both

Old Carthusians AFC, forwards)

and

Percivall Parr (Oxford University AFC, centre). |

|

team changes: |

Old Carthusians AFC's

James Prinsep withdrew from the original line-up because of

injury, his place going to Hunter. Greenwood took the place of

Royal Engineers FC's

Bruce Russell - both changes being announced the day before the

match.

"Buttery

magnanimously stood out to allow Greenwood playing thus displaying a

self-abnegation rarely found." |

|

team notes: |

Charlie Bambridge's brother,

Ernest, played for England in 1876. Harry Cursham's brother,

Arthur, also played for England 1876-79. |

|

appearance notes: |

Charlie Bambridge is

the fifth player to have made five England appearances, whereas Harry

Cursham is the thirteenth to have made three appearances.

Albemarle Swepstone becomes

only the

second goalkeeper

to earn a second appearance. |

|

records: |

For the first time, England have started

with only one debutant, having not done so with less than two so

far, thus making this the most experienced England

team so far.

The first time England have scored

fourteen goals in a season, and scored by a new seasonal/year record

of seven goalscorers.

On their sixth appearances, both Norman

Bailey and Jack Hunter become the most experienced England players to

have not scored a goal. |

|

"The English team, it is expected, will

arrive at the Central Station from London at eight o'clock to-night,

and take up their quarters at the Bath Hotel." - Friday, 10 March

1882, Glasgow Evening Citizen |

|

|

|

2-2-6 |

Swepstone -

Greenwood, Jones -

Bailey, Hunter -

Cursham, Parry, Vaughton, Brown, Bambridge, Mosforth. |

|

Averages: |

Age |

23 years 308 days |

Appearances/Goals |

3.5 |

1.6 |

|

most experienced so far |

|

"In the evening the teams were entertained to dinner in Robertson's

Bath Hotel, Bath Street, by the Scottish Football Association. About eighty

were present." - The Scotsman, Monday, 13 March 1882 |

|

|

|

England previous teams

vs. Scotland: |

|

1881: |

Hawtrey |

Wilson |

Field |

Hunter |

Bailey |

Holden |

Rostron |

Macauley |

Mitchell |

Bambridge |

Hargreaves |

|

1882: |

Swepstone |

Greenwood |

Jones |

Bailey |

Hunter |

Cursham |

Parry |

Vaughton |

Brown |

Mosforth |

|

|

|

|

Match Report

Morning Post, Monday, 13 March 1882

|

|

The

annual match

under

Association rules between

England and Scotland was played on Saturday afternoon at Hampden Park,

Glasgow, in the presence of about 12,000 spectators. The weather was

fine, and the ground in good condition. Scotland were successful in

the toss, and at first elected to play with the wind in their favour.

The home team speedily invaded their rivals' territory, and made

repeated attacks on their goal, which for some time was saved by the

dexterity of Swepstone. Good runs were then made by Parry and Cursham,

by they were stopped by the Scottish backs. Bailey also ran the ball

well down the ground, but took his kick too hurriedly, and it went

over the cross-bar. Once more the home forwards acted on the

aggressive, and a corner-kick seemed to imperil their fortress, but

Swepstone proved equal to the occasion. At length, however, there are

some determined play in front of the English posts, and out of a loose

scrimmage the ball was shot through by Harrower. Very clever runs were

made by Cursham and Bambridge down the centre of the ground, the ball

being well passed from one to the other with great skill. Mosforth

also made a fine attempt to score, and shot the ball into the hands of

the goalkeeper, who threw it well away. He returned to the charge, and

this time succeeded in sending the ball between the posts. The score

having thus been brought level, the play became even more determined.

A little before the time arrived for changing ends Kerr placed a

second goal to the credit of Scotland. The sides having crossed over,

the home team had the wind against them, but this did not prevent

Harrower from immediately kicking a third goal, and the game had not

proceeded much further before Ker added a fourth, and within five

minutes of the cessation of hostilities Kaye sent the ball through.

This was the last score, and thus, when time was called, victory

rested with the Scotch by five goals to one. The

annual match

under

Association rules between

England and Scotland was played on Saturday afternoon at Hampden Park,

Glasgow, in the presence of about 12,000 spectators. The weather was

fine, and the ground in good condition. Scotland were successful in

the toss, and at first elected to play with the wind in their favour.

The home team speedily invaded their rivals' territory, and made

repeated attacks on their goal, which for some time was saved by the

dexterity of Swepstone. Good runs were then made by Parry and Cursham,

by they were stopped by the Scottish backs. Bailey also ran the ball

well down the ground, but took his kick too hurriedly, and it went

over the cross-bar. Once more the home forwards acted on the

aggressive, and a corner-kick seemed to imperil their fortress, but

Swepstone proved equal to the occasion. At length, however, there are

some determined play in front of the English posts, and out of a loose

scrimmage the ball was shot through by Harrower. Very clever runs were

made by Cursham and Bambridge down the centre of the ground, the ball

being well passed from one to the other with great skill. Mosforth

also made a fine attempt to score, and shot the ball into the hands of

the goalkeeper, who threw it well away. He returned to the charge, and

this time succeeded in sending the ball between the posts. The score

having thus been brought level, the play became even more determined.

A little before the time arrived for changing ends Kerr placed a

second goal to the credit of Scotland. The sides having crossed over,

the home team had the wind against them, but this did not prevent

Harrower from immediately kicking a third goal, and the game had not

proceeded much further before Ker added a fourth, and within five

minutes of the cessation of hostilities Kaye sent the ball through.

This was the last score, and thus, when time was called, victory

rested with the Scotch by five goals to one.

|

|

|

Match Report

The Times, Monday, 13 March 1882

|

The international football match between

England and Scotland, under Association rules, was played at Glasgow

on Saturday before 15,000 spectators. Both countries were well

represented, but the Scotchmen were the favourites. A stiff breeze

prevailed during the progress of the game, but even with this

advantage in their favour the Scotchmen did not make much of it,

half-time being called with the score at - Scotland, two goals;

England, one. The second half, however, proved disastrous to the

Englishmen, who seemed to have shot their bolt in defending their goal

in the first half, because they did not play so well and could not

retain the ball when they did get possession. The consequence was that

a third goal was soon added, and in a short time a fourth fell to the

Scotchmen, who, hemming in their opponents, surrounded their goal

continually. Five minutes before the call of time a fifth goal fell to

Scotland, and the match was brought to a close before the Englishmen

could increase their score of one goal.

|

|

North British Daily Mail, Monday, 13 March 1882

|

|

There can be

little doubt, if the contest had been played under Scottish rules, it

certainly would have been a much prettier game to look at. |

|

|

|

In Other News....

|

It was on 10 March 1882 that Roderick

Maclean was charged with high treason in attempting to assassinate Queen

victoria by shooting at her carriage the previous week. He was found

'not guilty, but insane' and sent to Broadmoor Asylum for the rest of

his life. |

|

|

|

|

Source Notes

|

TheFA

Scottish FA

Cris Freddi's England Football Factbook

Andy Mitchell's extensive research

JAH Catton's

The Story of Association Football

100 Great Black Britons |

|

Professional Footballer's Association

LondonHearts.com

The Football Association Yearbook

James Corbett's England Expects

Original Newspaper Reports

Anton Gorovik & John Treleven |

|

|

cg |